Most people don’t understand how the Social Security system works. Because of this, it’s easy to believe untrue things about it. As a public service, Muttroxia is providing this Social Security timeline and “FAQ”.

Early 1980s: The Social Security Administration looks ahead (as it constantly does), and due to trends it forsees, notably the retirement of the Baby Boomers, they predict they will need more funding in the future.

1983: Alan Greenspan leads the way to increase payroll taxes to build up the Social Security Trust Fund, building the surplus it will need when the Baby Boomers retire.

Today: Aside from a bunch of alarmist rhetoric, nothing special is going on. We’re about $2 trillion dollars in the black. Let’s look towards the future.

2017 (approximate): We no longer put as much money into the system as we take out. Note that this does not mean there is no money there. We have spent about 34 years building up the reserves to about $2.5 trillion dollars, and now we start drawing down against it.

2042 (approximate): The reserves are gone. There is no longer enough money coming in to cover what’s promised to go out. We then have a shortfall of 27% in payments. That 27% each year causes the gap to grow each year. (In the graph below, the line represents accumulated surplus/deficit, not the surplus/deficit for that particular year.)

So Social Security is fine for the next thirty five years, and then there is a shortfall. Not a lot of government programs are solvent for the next thirty five years, eh? For example, Medicare and Medicaid, which are often lumped into an amorphous “entitlements” category when you’re trying to scare people, are in much worse shape. In fact the picture is even better. The 2042 date is a conservative estimate, as it should be. Other methods of estimation project that Social Security will never run out of money. (More detail on this here.)

Leaving that aside, what does a shortfall of 27% look like? Not much. When you have 35 years to address a problem, it’s pretty simple. Very small changes in the amount going in or going out are enough to eliminate that future shortfall. For instance, right now you pay Social Security taxes on your first $90,000 of income each year, anything after that is a free ride. Eliminating that cap, or raising it marginally, would be enough. Or you could raise the retirement age. Or you could means test. The portion of the Bush tax cuts going to the richest 1% of taxpayers alone will cost 0.6% of GDP—more than the CBO projected shortfall of 0.4% of GDP.

There’s any number of solutions, but what they share is that not much pain is required. If the gap even exists, it isn’t big, and we have plenty of time to close it. We’ve been in this position before. This isn’t the first time that we’ve looked far into the future and taken action. The scale of the problem is smaller than it has ever been.

Let’s change topics. You might wonder what this mysterious fund looks like. Is there a federal bank vault filled to the brim with gold? Is it all just an accounting fiction? It’s a little bit of both. The Social Security Administration takes the money coming in and buys US Government bonds. Then it stores the bonds. When it needs to, it redeems the bonds.

There’s a couple things to note about these bonds. First is that they are the most secure investment in the history of mankind. That’s not an exaggeration, there has literally never been a investment with lower risk. Second is that there is nothing magical about the bonds just because the Social Security Administration owns them. They are the exact same bonds that are owned by China, by Japan, and probably you. If you don’t have them in a drawer somewhere, the odds are good that any investment portfolio you’re part of will have some of them.

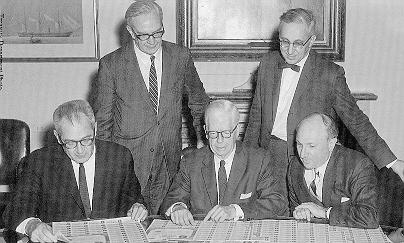

Above: Treasury Department and Social Security officials examining some of the Treasury bonds purchased by the Social Security Trust Funds in 1968.

There are many who claim that the SSA doesn’t have any real money. “There is no trust ‘fund’ — just IOUs that I saw firsthand,†Bush said.

If those bonds are worthless IOUs, then the US Government is going to intentionally not pay off the bonds, not make good on it debts. That’s known as default, and it’s a big deal. Not only is this unconstitutional (“The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for payment of pensions and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection or rebellion, shall not be questioned.”), terrible economics and likely to set off a world depression, but it couldn’t ever happen politically. As long as those bonds are owned by US citizens, and the more influential citizens at that, they will never let them be defaulted on. So the money is safe, safer than any other monetary vehicle.

But wait, you may say, we still have to have money to pay for those bonds as they come due! Where is all that money going to come from?

And this is a valid problem. The money comes from the general fund of the United States. So we have to come up with it. Now the idea of issuing bonds is that the government gets the money now and pays it back later. It then spends that money in various productive ways, creating a societal return on investment that’s as big or bigger than the return it has promised the bondholders. Suppose the society has not spent the money wisely? Then there is indeed an issue, for one day the bill comes due. (One unwise thing to do would be to count the SSA assets as being part of the general budget. Since that surplus has already been designated for SSA use, it should not be available in the budget to be spent on other things. That would be double-counting. This is what Al Gore meant by a “lockbox”, essentially making sure that the SSA accounting was kept separate from the rest of the government. Gore did not win, and there is no lockbox.)

This issue of how the USA will find the money to make good on it’s debts has nothing to do with Social Security. This issue is a general problem about how the country uses it resources and plans for the future. Remember, there is nothing special about the bonds that the SSA holds. They are the same bonds everyone else has. So to the degree this is an issue (and I certainly believe it is), it is a general issue about the whole country and it’s future, there is nothing in it that ties it to Social Security.

In other words, Social Security is in great shape. It’s the rest of the government that’s in trouble.